Part 1 – before 1870

The early days

With cooking, heating, and lighting all requiring the use of naked flames, the risk of fire was always ever present. Despite the significant danger to lives and property, there was no requirement for any public body to provide a fire brigade. Other Devon towns suffered some catastrophic fires, including Tiverton where 600 houses were destroyed by fire in 1612, and another 298 houses were destroyed in 1731. 450 houses were destroyed at Crediton in 1743, and 180 houses at Honiton in 1765. Thankfully, Bideford was spared that scale of devastation.

In the early days, if your home or business caught fire, then you were largely dependent on your own efforts to put the fire out. Neighbours and passersby may lend a hand, but all too often the fire burnt until there was nothing left to burn. Firefighting techniques were generally limited to using buckets to throw water on to the fire, pulling thatch off the roof, and creating fire breaks to stop the fire spreading. Rescuing furniture and other possessions was often all that people could do to help.

The earliest record of a serious effort to improve the situation in Bideford was in 1764, when the Bridge Trust purchased a fire engine for the town. It would have been a manually operated pump on a small carriage, like the one in the photograph below.

An early manual fire engine (Tony Morris photo)

However, it still depended on volunteers to pull and push the fire engine to the fire and to then continuously move the handles up and down to pump the water onto the fire. Even more volunteers were needed to collect water from wells, ponds, streams etc., using buckets, saucepans, or any other suitable container, to keep the fire engine’s cistern continuously supplied with water.

The reliance on enough people coming forward to operate the fire engine, and the shortage of readily available water supplies would frequently limit the effectiveness of firefighting efforts. However, when water supplies were available, the fire engine could be used to project water onto the fire in a far more effective way than could be done by simply throwing water from buckets. The Bridge Trust subsequently purchased an additional two fire engines for the town.

In 1823, a newspaper report about a farm fire on the Bowden estate referred to “fire engines being sent out from Bideford”, and how “some hundreds of respectable people attended and gave all possible assistance.” The report goes on to say, “An infant, forgotten in bed in the hurry, narrowly escaped the flames; but was happily discovered by a man on the point of throwing the bedding out of the window.” However, despite the efforts of all involved, the house, barn, stable, and shippen were all destroyed.

This was a common ending for fires in those days, as enthusiasm and effort could not overcome the lack of organisation, lack of training and frequently a lack of water. Sadly, reports of children losing their lives after their clothes caught fire, whilst near an open fire, were all too common. Frequently, parents had left young children alone in the home when this occurred.

‘The North Devon Journal’ - 31 March 1842

Whilst most of the deaths involved children, there were a few adults who also lost their lives when their clothes accidentally caught fire. It was rare for someone to survive such incidents, but in the few cases where they did, the victim was often left badly scarred. It was not until the Children Act of 1908 that any attempt was made to reduce the number of young deaths, although that only made it an offence to leave a child under the age of seven in a room with an unguarded fire.

Insurance Companies to the rescue

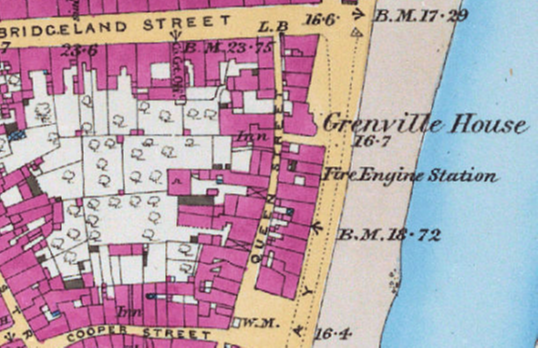

It is often believed that fire insurance companies only provided fire brigades in large towns, but they did more. Dependent on the amount of fire insurance business they had in a town, they sometimes presented a fire engine to a town. In Bideford, not only did the West of England Fire and Life Insurance Company provide a horse drawn fire engine in 1847, they also recruited men to crew it. The men were paid a retainer, received some training, and were summoned when needed. The fire engine was garaged by the company’s offices on the Quay.

Fire Engine Station of the West of England Fire and Life Insurance Company

One of the first calls for the new fire engine was to Appledore, in March 1847, when a malthouse caught fire in Bude Street. The company’s agent, John Hamly, also attended. At the end of December 1847, at around 10 pm, a fire was reported in Mill Street. It was caused by an accident with a candle as an elderly lady, Mrs Pinkney, was getting into bed at the lodging house of Miss Peacombe. A newspaper report said that “in the almost incredible space of a few minutes their effective and powerful fire engine was on the spot.” The fire was contained to the room, which was badly damaged.

The new Town Hall was opened in 1851, and it included an Engine House for the Borough’s fire engines. However, the arrival of the insurance company’s horse drawn fire engine and their provision of firemen may have been fortuitous, as concern was growing about the effectiveness of the Borough’s fire engines and the lack of a brigade to operate them.

A horse drawn manual fire engine (Tony Morris photo)

On 10 April 1851, a fire broke out at a sail loft and rope manufactory at Chircombe, owned by the Mayor, Thomas Evans. West of England and Borough fire engines arrived and although they were unable to save those buildings, they did stop it spreading to Mr Cox’s adjacent shipbuilding yard and a nearly complete 1,000-ton ship. Damage was put at £3,000, equivalent to £355,000 today. It was reported that the firefighting effort was hampered by a lack of water. It should be remembered that there were no water mains in the town then. Residents obtained their water from around 500 hundred wells in the town, some public and some private. Larger houses often had a hand pump to draw water from underground, as well as a small reservoir to collect rainwater.

In November 1851 there was another fire at Cox’s shipbuilding yard, and it was reported that three individuals “started with all possible speed” with the town engine. They arrived shortly ahead of the West of England engine. It was also reported that “persons of every rank and age ran to the spot from all quarters.” The fire was successfully extinguished, but it was claimed that it could have been achieved much quicker if there had been a proper supply of buckets to carry the water from the river to the engines.

At a Town Council meeting in November, Councillors complained about the condition of the Borough’s three fire engines, which were described as “cumbrous in their movement, unprovided with men, and entirely destitute of buckets.” This followed two recent fires where it was claimed that they had been found “of very little service.” Some Councillors called for the town engines to be put in order and for the formation of a fire brigade. A sub-committee of Mr. Taylor, Mr. Thompson, and Mr. Narraway was established to review the issue and report back. It appears that whilst some maintenance work was then carried out on the town’s three fire engines, the sub-committee’s discussion on improvements was centred on buckets. How many, whether they should be made from leather or gutta percha, and the cost (between 12 and 16 shillings each) preoccupied the sub-committee and the council. After much discussion the council agreed to buy 24 buckets.

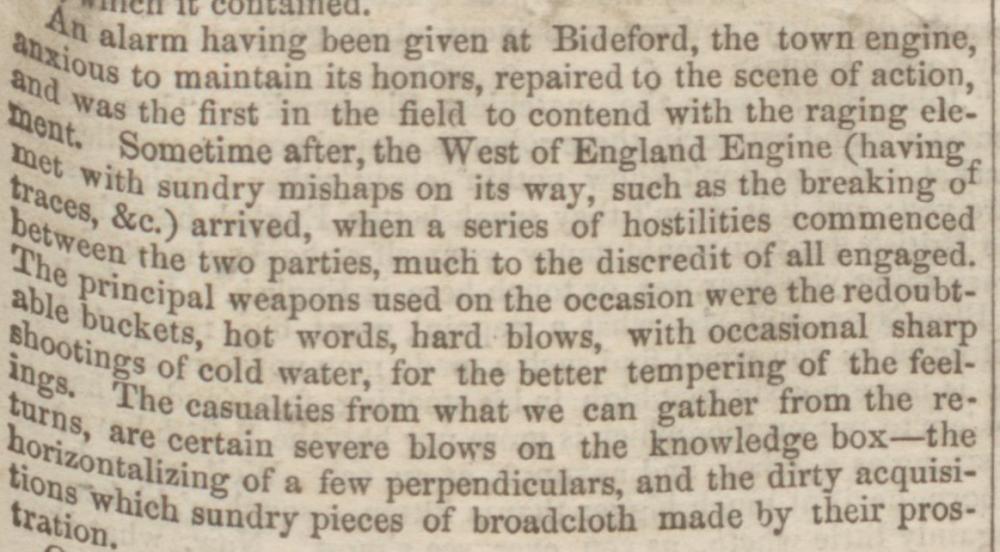

In February 1852, the usual co-operation between the West of England brigade and people operating the town engine broke down at a fire at Kenwith Castle Farm. Unusually the town engine arrived first, the West of England engine having had mishaps on the way. Sadly, the friction escalated from name calling and throwing water at each other to blows being exchanged.

'The North Devon Journal' - 19 February 1852

An Inquiry into the disorder was conducted by the Mayor, T. Evans Esq., T.B. Chanter Esq., James Gould Esq., Major Wren, and the Rev. J. T. Pine Coffin. According to the North Devon Journal the inquiry failed to identify the worst offenders, failed to draw up any rules for working together, and simply said all parties should “begin afresh.”

In 1860, the Council observed an exercise of the town’s two fire engines and the West of England’s larger fire engine and although they performed well, there was insufficient water to supply all three. This highlighted the lack of fire plugs (hydrants) “as in most other towns,” however it would be several years before this changed.

Town fire brigade established

The lack of a proper fire brigade to use the town’s fire engines prompted the Local Government Board to form a fire brigade in 1862. Those appointed were Messrs. E. Major, A. Cawsey, J. Fulford, T. Crossman, J. Lile, W. Burnard, P. Bowen, W. Williams, W. West, J. Elliott, H. Prouse, and J. Berry. They were paid 10 shillings a year, and the Fire Engine Committee were authorised to make changes of personnel at their discretion. Six shillings per annum was given to the committee to distribute to those they “think proper.” Although not specified, I suspect this was to reward the men for exceptional service, or volunteers for their assistance.

Having looked at the 1861 census, I believe the men were:

Edward Major, a 25-year-old Mason living in Coldharbour.

Archibald Cawsey, a 22-year-old Stone Mason living in Union Street.

John Fulford, a 44-year-old Joiner living in Tower Street.

Thomas Crossman, a 27-year-old Stone Mason living in Willett Street.

Either John Lile, a 50-year-old Plumber, or his son James Lile, a 17-year-old Shipwrights Apprentice, both living in Torrington Street.

William Burnard, a 40-year-old Grocer living in Meddon Street.

Peter Bowen, a 42-year-old Painter living in Union Street

William West, a 38-year-old Wheelwright living in Potters Lane.

John Elliott, a 57-year-old Mason Journey Man living in Bull Hill.

Hugh Prouse, a 55-year-old Boot Maker living in Mill Street.

There are two possibilities for J. Berry, either James Berry, a 30-year-old Furniture Brokers Assistant, living in Chingswell Street, or John Berry, a 44-year-old Mason living in Torridge Street.

Surprisingly, there were twelve William Williams living in Bideford in 1861! I suspect the fireman was either a 41-year-old Master House Painter living by the Market, or a 25-year-old Mason living in Union Street.

The following year, the Local Government Board confirmed the Fire Engine Committee members would be Messrs. Taylor, Norman, Major and Walker. They also agreed to continue hiring men to be in the fire brigade.

In April 1864 the West of England Fire Brigade were called to Ashridge, where a house and farm were alight. Fortunately, there was a pond with plenty of water and with the help of many volunteers the engine was kept well supplied. However, the house and farm buildings were mostly thatched, so the fire spread quickly. They managed to save a barn, but the house, outbuildings, a cow shed, and 150 bales of straw were destroyed. The supposed cause was a not uncommon one, a spark from the chimney igniting dry thatch. Unfortunately, the tenant Mr. Foster, who had only taken over the farm in March, was not insured.

In 1865 there was concern that “the fire engine was in a very Bad State,” which was blamed on the Borough Surveyor hiring it to shipbuilders 'to stanch vessels' where salt water corroded the iron work. The Board ordered the engine to be repaired. Sadly, in 1867, another child, about 3 years old, was burnt to death in a High Street home when the child’s clothes caught fire.

Whilst it was not unusual for women to help by carrying water to keep the fire engine filled, it seems that in 1866, at Clovelly, women played a bigger part when a fire broke out in a boat house. The North Devon Journal said, “Great praise is due to the female portion of the population, who worked as if life and death were involved.” With no fire brigade and no fire engine and, I suspect, many men from the village out fishing, they had to play a bigger part. The only men to get a mention for assisting were from the coastguard.

'The North Devon Journal' - 15 May 1866

Just before Christmas 1867, there was a fire in a house in Chingswell Street that was quickly dealt with by the West of England Fire Brigade. As the house had been unoccupied for some time there was immediately suspicion of arson, or incendiarism as it was then called. Superintendent Vanstone immediately began an investigation, and suspicion quickly fell on a stranger seen in the town who said, when arrested that his name was William Caius. The reason he did not give his full name, Liberty Caius Kingsford, became obvious when it was established that he was the nephew of the new owner of the house, William Kingsford. The motive had been the £650 insurance policy on the property, but the result was a seven-year prison sentence.

One evening in November 1869, the stables at the rear of Tanton’s Commercial Hotel were discovered to be on fire. According to the North Devon Journal, the town fire bell was sounded, and thousands were reported to have rushed to the spot. It was fortunate that there was a high spring tide, as that provided plenty of water for the West of England and the two Borough fire engines. The fire was stopped from spreading to the hotel, but the stables were destroyed. However, the Devon Weekly Times reported that the Borough engines “were sadly out of order and rendered but little service.”

Acknowledgments

It is not unusual to find that errors have crept into previous publications, so I am pleased to have the opportunity to correct some. Sadly, one publication in particular, a book called “Devon Firefighters”, has a lot of mistakes regarding firefighting history in Bideford. However, I am grateful to Ian Arnold for his excellent book, “The Bideford Fire Brigade”, which contains a lot of accurate information.

The late Peter Christie was a great help with valuable information that he had acquired during his local history research. I would also like to thank the staff of the North Devon Record Office, and the Devon Heritage Society, as well as members of The Fire Brigade Society for their assistance. Volunteers at the Bideford and District Community Archive have always been very helpful and, last but not least, the many former Bideford Firemen who indulged me when I was growing up and answered my many, probably annoying, questions.

26 August 2025

"Tony Morris was born in Bideford and grew up within sight of the fire station, which was the inspiration for his lifelong interest in the fire service. In those days, Bideford’s firemen were called to the fire station by a loud siren, of the type used during the war for air raids. Initially it was all about watching the firemen rush to the fire station and the fire engines dashing off to fires and other emergencies. However, as Tony got older his interest grew into a desire to understand every aspect of fire services, both here and abroad. There then followed a 32-year career in the fire service, followed by a 14-year career as an Emergency Planner. Now, fully retired, he has been further researching the fire service in Devon, and particularly Bideford’s firefighting history."