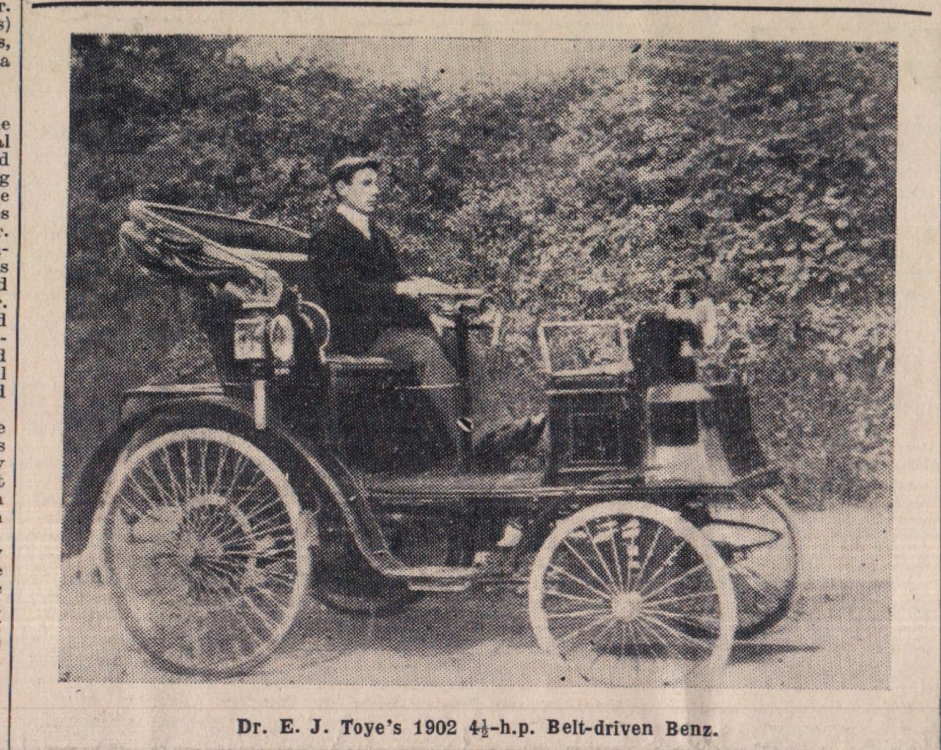

Bideford’s First Car

Interesting reminiscences by the late Dr E.J. Toye

Only a few weeks before his most lamented death Dr E.J. Toye was good enough to grant an interview to a Representative of the “Bideford Gazette,” and for the benefit of our readers recall some of his interesting experiences during his pioneer motoring days in North Devon.

In these days of learners’ licences, Belisha beacons, automatic traffic signals and a hundred and one other precautions to control traffic it hardly seems possible that only thirty-six years ago the people of our district were vastly impressed with “one of those new motor cars” when it took to the streets in 1902. It does not look very imposing according to modern standards but it had some adventures and deserves a place in Bideford’s history.

It belonged to Dr E J Toye, former Mayor of Bideford and founder-President of Bideford Rotary Club to mention but two of his many spheres of public interest. As far as he knew it is looked upon as the first motor car in Bideford, and he claimed to be certainly the first medical practitioner in North Devon to use a motor car.

When in 1902 his first car made its appearance on the roads of the town he believed there were only three or four other people in the neighbourhood who possessed cars. He believed there was one in the Stucley family, and Misses Houldsworth and Capt. Prideaux-Brune also had cars. First he had what was called a 3½ h.p. Benz but its stay was brief for it was not good enough for our hills and a 4½ h.p. model of the same make was substituted. It was a temperamental affair. If he wanted to go ahead it would stop; if he wanted it to sop it would go ahead. It was concerned in several escapades that threatened to terminate the good doctor’s interest in motoring, medicine or anything else. Those who take up motoring today can have little idea of what those early pioneers went through. Motoring in those days appeared to be only a subtle way of getting walking exercise for often the driver did more walking than motoring.

One celebrated Market Day, recalled the doctor, he started to descend High Street slowly and quietly because in those days they could never rely on the brakes. His man whispered to him that the brakes were not acting and they discussed whether they should go on or into the houses at the side. By the time they had thoroughly discussed the problem, however the motor had decided the choice for them, having attained such impetus there was no alternative but to go down the hill without a brake acting. They shared the heat the burden; his man steering and the doctor blowing the horn which he did vigorously and continuously. They missed the foot of a ladder upon which a painter was at work by inches, and by good fortune there was not a vehicle in the road. At the bottom with a speed of 30 or 40 miles an hour, they had every prospect of going into the river, but, fortunately they turned the corner on two wheels, ran along the Quay and sopped almost up Bridgeland Street. A man who had watched the descent of High Street came to the doctor next day with a nervous break-down! The doctor also heard that a lady said he ought to have been stopped by the police and he need hardly say how grateful he would have been to have been stopped by them or anybody.

The perils of going down hill have been described; now to deal with the trials of going uphill. The engine was a single cylinder model with three forward gears and reverse. If the hill was so steep or the engine rather off-form the doctor and his man would get out, still leaving the engine running, and walk alongside the slowly moving vehicle, still managing to steer it and probably giving it a helpful shove too. Another method was to turn the car around and proceed up the hill in reverse. “On a steep hill a trotting horse would pass us easily, much to our disgust of course” added the doctor.

In those days the roads were very rough and you knew it too when the car was fitted with solid tyres. Stones were put on the road and it was left to traffic to grind them in. Especially in the summer clouds of dust would result from the progress of cars and carriages. One ingenious person living at Northam Lodge or nearby overcame this by putting a chemical composition on the road which absorbed moisture from the air; thus there was no dust in that particular section.

He paid £400 for that car, it cost him 7s. 6d. a mile to run, he kept it for two years, and then sold it for £20, giving the people who sold it ten per cent commission and paid £5 for sending it to London for sale. So motoring was not exactly cheap and the depreciation value worse than it is today!

Gazette article dated 8 February 1938